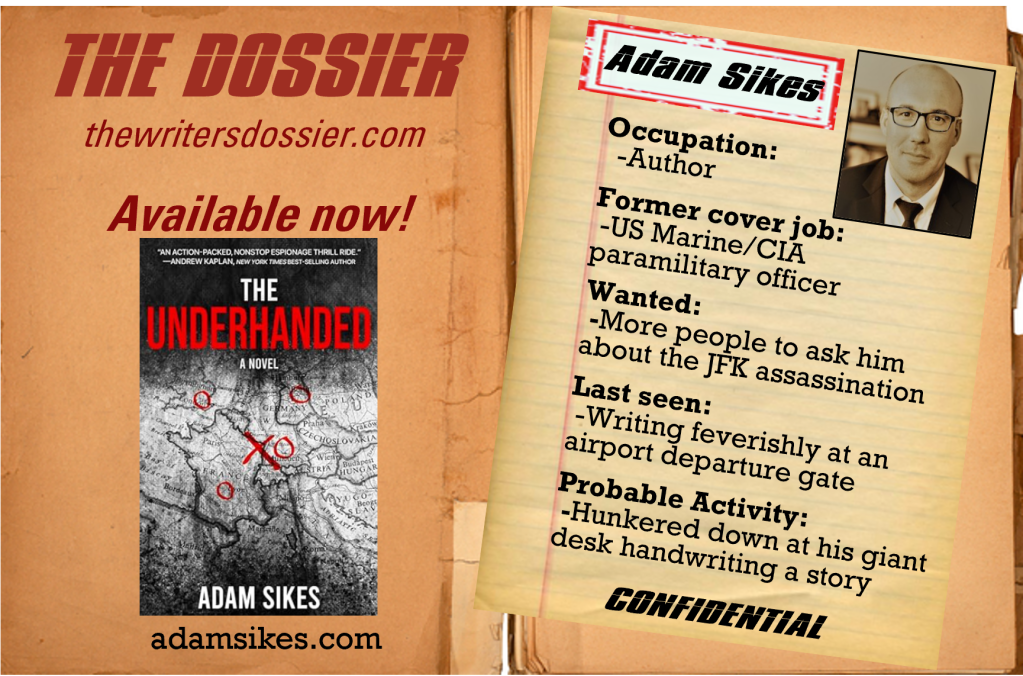

Adam Sikes

Landslide & The Underhanded

DOSSIER: One of the books in The Reading Corner of your website is ON WRITING by Stephen King. What’s the best piece of advice from that book that you’ve found helpful? Do you have anything different you’d pass on to others?

SIKES: On Writing is an exceptional book, and I encourage anyone interested in the craft of writing to pick it up. Even if you don’t prefer the kinds of books Stephen King writes—he is undeniably a brilliant writer. And in On Writing, he discusses the craft of writing in a manner approachable for anyone serious about writing fiction

But of all the wisdom and gems he imparts, what resonates most with me and what I tell everyone who expresses an interest in writing is this:

“If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot. There’s no way around these two things that I’m aware of, no shortcut.”

I fully agree with this. If you’re not reading a lot, particularly in the genre and/or style that you want to write in, then you won’t know what works, what doesn’t, what’s already been done, what’s been overdone, and everything else you need to know to make a good (perhaps great), original piece of writing. And for the act of writing, you just have to do it knowing the first draft will not be the final. Just do it. As Hemingway said, “Work every day. No matter what has happened the day or the night before, get up and bite on the nail.”

DOSSIER: Many writer followers of The Dossier are veterans or have other obligations to submit their writing for review by one tentacle of the US government or another. Having been a US Marine and a CIA paramilitary operations officer, who has to approve your material and, more importantly, do you think they’ve already read it before you’ve even sent it to them?

SIKES: As you suspected, yes, everything I write that pertains to intelligence and/or the military—both fiction and non-fiction—must be reviewed to ensure I have not discussed anything classified or sensitive relevant to national security. Since I last served at CIA, I only have to go through the Agency’s publication review board. Fortunately, I went through this process a few times while I was still working at the Agency, so I’m familiar with how it works. And if “they” are reading my material before I formally submit it for review—I’m flattered and hope they are duly entertained.

DOSSIER: When and where do you write, and what kind of environment do you prefer? (Music/silence/a west coast beach bar?)

SIKES: I write anywhere and everywhere. I travel a lot, so I write on planes, in hotel rooms, restaurants, coffee shops, outside at parks, I’ve stopped mid-run on a trail to outline a scene … I write whenever I can because I’m thinking about writing almost all the time.

But in my house, I have a special place where I truly enjoy reading and writing. In my home office, I have a substantial desk (as big as a small table) with my computer, stacks of papers, stacks of books, an antique bankers lamp, and enough room for my French press coffee. I write best and am most creative before the sun comes up and in the hour after sunrise. I also only use my lamp for light so that the room stays dark (until the sunlight starts coming through the window).

And for my novels, I handwrite my first draft in notebooks using a pen my brother made for me. He’s a wood craftsman and makes custom pens, among other things (like custom furniture), and I’ve drafted my last two novels with the same pen. But I go through numerous notebooks—my average novel will consume two or three 100-page notebooks, and I use my version of shorthand and write very small …

DOSSIER: A lot could be said about a US Marine becoming an accomplished author, but we’ll leave that for the social media comments. In your case, what propelled you into a writing career more—the fact that you grew up reading as a kid or all of the crazy shit you’ve seen and done throughout the world?

SIKES: This is an interesting question. When someone asks me about my writing journey, I usually tell the story of where I started drafting my first scene for my first novel, but that story is best told in person. But as for the principle driver for why I wanted to become a professional author … I think it was the combination of being a lifelong reader, already being a prolific writer (professionally, academically, and personally), and feeling like I had something to say given some of my life experiences.

Putting these elements together, it comes down to wanting to make other people happy. When I was in the Marine Corps and then with the Agency, if I had a good day, it often meant I’d probably ruined someone else’s day. And with the Agency, it likely had some kind of murky, morally ambiguous undertone. I still wholeheartedly believe in the mission, but after twenty-five years in this world, I was tired and decided that I’d served in that capacity for long enough. I wanted to focus on people’s enjoyment and happiness—to create something for the world and make people smile.

Now, whether my books about spies, conflict zones, troubled characters, villains, and all kinds of bad stuff actually make people feel happy … time will tell. But I hope it’s at least entertaining and genuine.

DOSSIER: You run the writer’s conference circuit, you do a lot of book signings and public appearances, even some speaking engagements. Have you ever had someone come up to you and tell you something about the CIA or the government that sounded a little … conspiratorial or just plain wacky? Afterward, did you think, “that’s a good plot idea!”?

SIKES: You’re correct, since leaving CIA I’ve done quite a lot of speaking engagements about my books (which involve spies and espionage) as well as discussed the Agency, the good and the bad, fact vs. fiction … Sometimes, I will get conspiratorial questions like who really killed JFK, but not as many as you might you think. The questions or comments I have found most fascinating typically come from someone of an older generation. They often approach me after my talk, pull me aside, and share with me an experience they had in Vietnam, or Cuba before Castro or under his rule, or perhaps in Europe in a country that bordered the Soviet Union, or maybe even Nashville … Something tense happened, or they were working for an organization with a shady structure, or they were told to keep things secret. Maybe Russian foreign exchange students were involved, a development non-profit was providing money to a European political movement, or a colleague disappeared in Africa … and they want to know if I think the CIA was involved or behind it. I will say what I can, but I usually refer them to books or resources where they can research said topic.

However, I would never use his or her story for a plot without their permission. But on occasion, I have thought—wow, that’s wild—which may influence a facet of a character or element of a story. And if this tidbit is really good or unique and becomes a key piece in the final draft, I give the person credit in the acknowledgments.

Website: adamsikes.com